Play and its Lessons

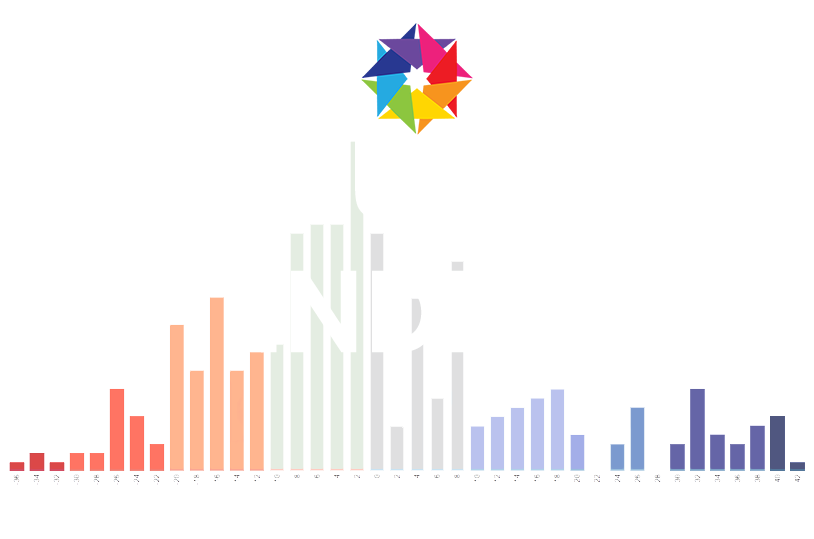

Across the Upper, Middle and Lower School Inclusivity Index surveys there are over 30 assessed school qualities. Among the most fascinating is the Play quality in the K – 4 survey. The richness and complexity of play among young students creates deep interactions which frame the positive and negative statements of the K - 4 survey shown below.

Inclusivity Index advisors developed these statements after much thought about modes of play as well as their observations from both research and their lived experiences. They concluded that the various types of K-4 can be segmented into three types: fantasy, physical and affinity.

Fantasy play offers children a shared experience where they create and through critical dialogue, develop their understanding of differences among people and backgrounds that make up their community. Children’s experiences are most robust where cultural distinctions are significant. Participation with children from different backgrounds and with different skills and interests illustrates unique dimensions for each participating child. These interecations reveal new facets of students’ worlds which develops cultural competence, encourage dialogue, feedback and listening and give the children experience with building consensus.

Physical play introduces higher levels of emotional response through conflict as well as sharing of successes and failures. These activities enage children in power dynamics and force them to work together to problem solve as well as learn about fairness.

Affinity play engages children with interpreting and observing characteristics of children that may seem to be most like them, highlighting commonalities and differences. These sharing moments help to explain aspects of their own family’s culture, better comprehend their place in school relative to others, and define themselves in a nuanced manner. Affinity play is an experience of both discovery and confirmation.

The Inclusivity Index advisors on play had other important observations. They concluded that schools approach play differently and that there is a wide range of skills among teachers in the task of overseeing play. Teachers, they note, often fall short of using play’s full development potential. The advisors hypothesized that some teachers see play as less important relative to classroom time and further, that many teachers are challenged with adminsitering fairness in their oversight of the activity.

Regardless, elements of play and their role in developing socialization skills are critical at this age as well as at all age levels including adulthood. Play helps to develop cultural competence and learning how to deal with power and conflict. It further teaches interaction skills in settings with dynamic emotions as well as concepts around fairness. All of these facets are encountered during periods of play.

The first three years of data from the K-4 survey reflect these hypotheses. We might expect the Play scores to be highly correlated with Fairness meaning students that are pleased with their play and report a healthy mix of play related activities during these desgnated times would also see the school as less biased and more fair. The data shows this is somehat true, but not always the case.

Below is a plot of the Play scores versus the Bias and Fairness scores for all K-4 students. 73% of students in the All Students Database record either neutral or positive Bias and Fairness scores (the right side of the chart) while 70% score their Play experience in the positive range and another 15% neutral (the top of the chart).

Note: the analysis chooses to deem 0’s (zeroes) as neutral and group these students with the positive score set. This respects the Inclusivity Index structure and the possibility that zero scores result from students avioding choices about that quality.

The data potentially informs the hypotheses of the advisors that voice concern over the intentional use of play as a development activity in schools First, 63% of the children scored both qualities either positive or neutral reflecting the aspiration for all schools that play is enjoyed and supports the broader sense of fairness at their school. The only 5% score both negative reinforces this endorsement althoughthose 5% might be seen as an important focus.

The other two quadrants provoke more thought. Consider the 22% who enjoy play and yet see bias and a lack of fairness in the community. Is the school connecting the two qualities appropriately? Further, what about the 10% that don’t find play as a positive although recognize the school’s environment as fair? The combined 32% are recognized by adminstrators as presenting improvement opportunities.

Can you develop the thought of why schools approach play differently? Which approaches are effective and ineffective? Why?

How should schools balance and explain the role of play in K – 4 with classroom priorities?

How can we help teachers improve their conflict resolution and application of fairness abilities?

Do you agree with this structure of three ypes of play? Too few? Too many?

Should play be studied at all age levels as opposed principally early childhood?